Taking a closer look at LHC

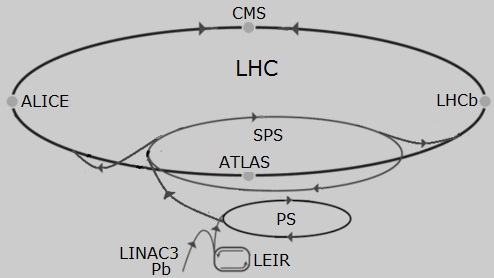

A sizeable part of the LHC physics programme implies lead-lead collisions with a design luminosity of 1027 cm-2 s-1. This has been achieved after an upgrade of the ion injector chain comprising Linac3 and LEIR machines (and also PS and SPS, obviously). Each LHC ring will be filled in 10 min by almost 600 bunches, each of 7×107 lead ions. Central to the scheme is the Low Energy Ion Ring (LEIR), which transforms long pulses from Linac3 into highbrilliance bunches.

In addition, since September 2012, LHC physicists are colliding beams made of two different particles – heavy ions with the less-massive protons. Proton-lead collisions are something the LHC was not originally foreseen to do, but now it has even higher physics interest than had been expected. All the experiments have joined the programme, including LHCb which originally wasn’t a heavy-ion experiment

One of the main objectives for lead-ion running is to produce tiny quantities of such matter, which is known as quark-gluon plasma, and to study its evolution into the kind of matter that makes up the Universe today. This exploration will shed further light on the properties of the strong interaction, which binds quarks, into bigger objects, such as protons and neutrons. Heavy-ion collisions provide a unique micro-laboratory for studying very hot, dense matter. This part of the LHC programme will be probing matter as it would have been in the first instants of the Universe’s existence.

Lead ions start as lead atoms, which in nature have an atomic nucleus containing 82 protons and between 122 and 126 neutrons, surrounded by a cloud of 82 electrons. The LHC only accelerates one type, or isotope (Pb-208), of lead that contains 126 neutrons. Since protons and neutrons have approximately the same mass, an LHC lead ion weighs roughly 208 times more than a proton.

| An atom of lead becomes an ion of lead when some or all of its electrons are stripped away, leaving the remaining portion of the atom positively charged. The LHC acceleration process gradually strips away all of the lead atoms’ electrons, leaving a beam composed only of lead nuclei.

The LHC’s lead-ion beams start with a piece of pure lead 2 centimeters long that weighs 500 milligrams. The lead “sample” is heated to about 500 degrees Celsius to vaporize a small number of atoms. An electrical current is used to remove a few of the electrons from each atom, and then the newly created ions begin the ride of their life. |

|

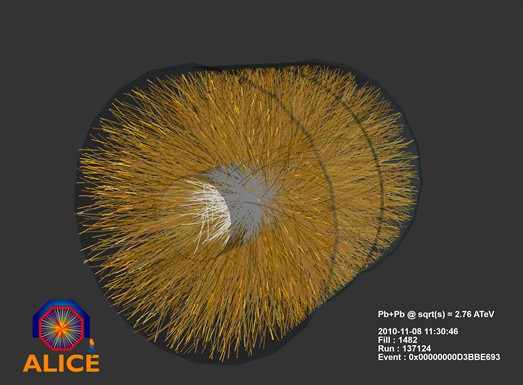

Events recorded by the ALICE experiment from the first lead ion collisions, at a centre-of-mass energy of 2.76 TeV per nucleon pair.

The ions first travel through a linear accelerator called Linac3, picking up a small amount of energy (4.5 MeV per nucleon) before having more electrons removed. Next, the ions are accumulated and accelerated to 72 MeV per nucleon in the Low Energy Ion Ring, or LEIR. These first three stages in the process – vaporization and acceleration in Linac3 and LEIR – are unique to ions, but as soon as they leave the LEIR they travel the same path as their lighter cousins the protons.

Despite their names, the next two accelerators – the Proton Synchrotron and the Super Proton Synchrotron – also accelerate heavy ions. In the PS the lead ions zoom to 5.9 GeV per nucleon and have the last of their electrons stripped away. The SPS accelerates the beams to 177 GeV per nucleon and finally injects them in two directions into the Large Hadron Collider.

Physicists prefer to quote heavy-ion beam energies “per nucleon,” where protons and neutrons are both nucleons, as this allows for an easier comparison with the energies of beams of protons and other types of ions.

With the nominal magnetic field of 8.33 T in the dipole magnets, these ions will have, for the eventual full energy operation,a beam energy of 7 TeV/proton (7 Z TeV, with Z = 82) or 2.76 TeV/nucleon (2.76 A TeV, with A = 208).

So, the total centre-of-mass energy will be:

2 x (7 x 82) = 2 x (2.76 x 208) ≈ 1150 TeV (1.15 PeV)

In the LHC the lead-ion beams will be accelerated and brought into collision in the center of three of the LHC’s four major particle detectors – ALICE, ATLAS and CMS, but, as it has been said before, LHCb has been included with p-Pb collisions. Even with the LHC running at half power, the first collisions of lead ions in the LHC were more than 13 times more energetic than the previous record set at RHIC (Brookhaven National Laboratory).

|

AUTHORS Xabier Cid Vidal, PhD in experimental Particle Physics for Santiago University (USC). Research Fellow in experimental Particle Physics at CERN from January 2013 to Decembre 2015. He was until 2022 linked to the Department of Particle Physics of the USC as a "Juan de La Cierva", "Ramon y Cajal" fellow (Spanish Postdoctoral Senior Grants), and Associate Professor. Since 2023 is Senior Lecturer in that Department.(ORCID). Ramon Cid Manzano, until his retirement in 2020 was secondary school Physics Teacher at IES de SAR (Santiago - Spain), and part-time Lecturer (Profesor Asociado) in Faculty of Education at the University of Santiago (Spain). He has a Degree in Physics and a Degree in Chemistry, and he is PhD for Santiago University (USC) (ORCID). |

CERN CERN Experimental Physics Department CERN and the Environment |

LHC |

IMPORTANT NOTICE

For the bibliography used when writing this Section please go to the References Section

© Xabier Cid Vidal & Ramon Cid - rcid@lhc-closer.es | SANTIAGO (SPAIN) |